Some people spend years searching for their calling. For Regina Stevens-Truss, the Dorothy H. Heyl Professor of Chemistry at Kalamazoo College, finding her calling was different.

“I’m not sure that it was a matter of finding what I wanted to do,” she said. “It was more like destiny. I have always loved science and math!”

That destiny has taken her on a remarkable journey. She’s gone from a 14-year-old immigrant—arriving in Brooklyn, N.Y., with limited English—to a nationally recognized biochemistry educator who has spent 26 years inspiring students at K. And career success is why the United Nations is celebrating women like Stevens-Truss today, February 11, the International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

According to the U.N., a significant gender gap has persisted throughout the years at all levels of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines all over the world. Even though women have made tremendous progress toward increasing their participation in higher education, they are still underrepresented in these fields. The U.N.’s hope is that role models like Stevens-Truss will continue inspiring young women to stay with STEM—in academics and their professions—for years to come.

The ‘Wait, What’ Kid

Born in Panama, Stevens-Truss arrived in the United States in 1974 with an insatiable curiosity that often tested her father’s patience.

“I was that kid who wanted to know ‘Why? How?’” Stevens-Truss said. “My dad would say to me in Spanish all the time, ‘Cállate, Regina,’ because I would always ask why. Yes, I was that ‘wait, what?’ kid in school.”

Her transition to the U.S., though, wasn’t easy. Placed in eighth grade despite limited English proficiency, Stevens-Truss faced isolation as a self-described scrawny Black Latina in 1970s Brooklyn.

“I got picked on a lot and had very few friends,” Stevens-Truss said.

But what could have derailed her education became her anchor.

“What grounded me was school, and in particular my math classes.”

Those early teachers, none of whom looked like her, saw something special and encouraged her learning. When her family moved to New Jersey, she found community among her white classmates at Cherry Hill West High School.

“Those were hard years because I was an outcast yet again,” Stevens-Truss said. “I only had three Black friends. My friend groups were all white women, and they helped keep me in science and math because we all loved these subjects. We were taking these classes together, we lived near each other, and I belonged.”

Finding Her Path

At Rutgers University, Stevens-Truss initially pursued medicine—like many first-generation students—to fulfill family expectations. Later, a turning point came at the University of Toledo while she was working as a part-time research technician for Richard Hudson ’61.

Hudson was a K chemistry alumnus who would later become her Ph.D. advisor. One day he walked into the lab with unexpected news and said, “Regina, you need to go do something else.” Thinking she was being fired, Stevens-Truss asked why. His response changed her life: “Because I can tell you’re bored. You need to go get a Ph.D.”

He was right.

“I love learning, and when it gets stagnant, I get bored,” Stevens-Truss said.

That restless curiosity that made her the “wait, what?” kid still drives her today, pushing her to constantly find new ways to reach students.

The Biochemistry Connection

What captivates Stevens-Truss about biochemistry now is the intersection where chemistry illuminates biology.

“Living systems are so complex and yet work so well that I, still to this day, find it exhilarating to learn about them,” she said. “My chemistry classes felt like work, and my biology classes made no sense to me. It’s always been awesome when I could connect my chemistry knowledge to biological phenomena—hence the reason I consider myself a medicinal biochemist. I love to understand living systems through how chemical changes impact them.”

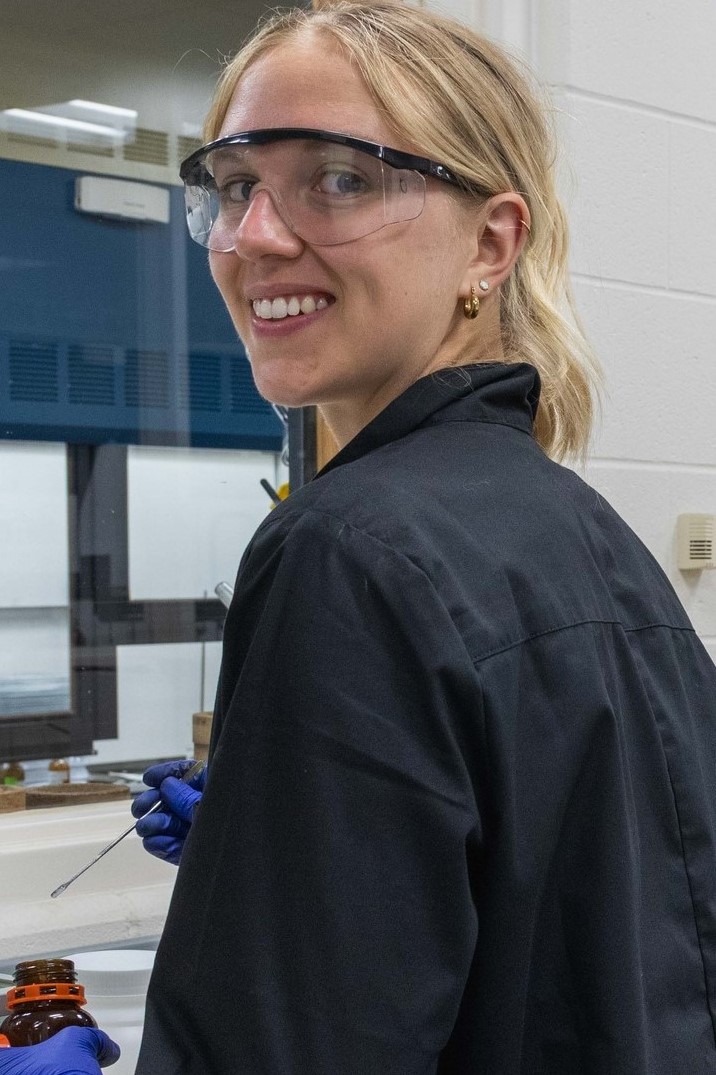

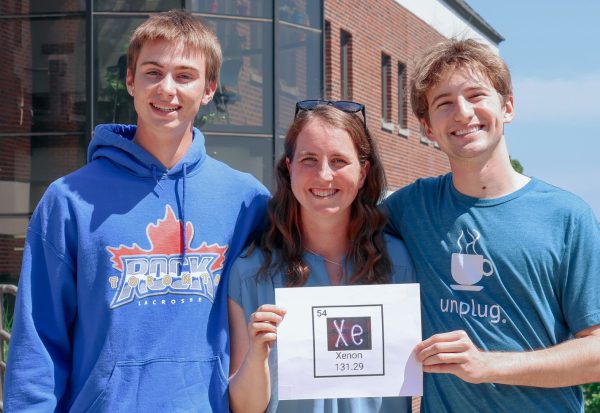

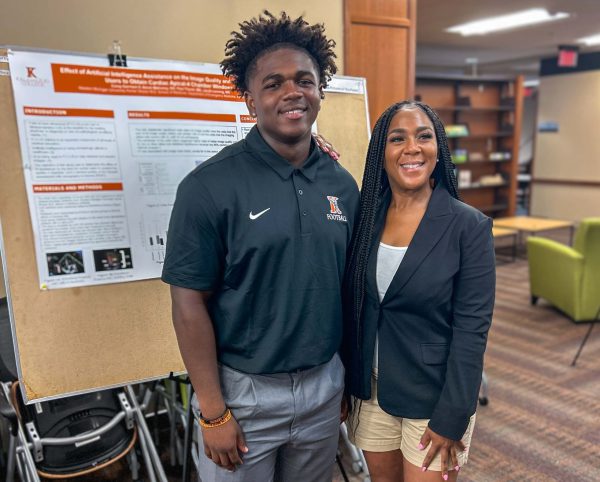

This philosophy permeates her teaching. Ask her biochemistry students, and they’ll tell you she constantly pushes them to ask how and why—the same questions that defined her childhood. Her current research focuses on ESKAPE pathogens, as she and her lab students study how antimicrobial peptides and hybrid compounds—developed in the K labs of Kurt D. Kaufman Associate Professor of Chemistry Dwight Williams and Associate Professor of Chemistry Blake Tresca—work against dangerous bacteria like E. coli and S. aureus.

Twenty-Six Years at K

Hudson had more career advice for Stevens-Truss when she was a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Michigan.

“Richard called the lab one day and said to me, ‘Regina, I have the job for you: teaching chemistry at Kalamazoo College.’”

Her response was, “Kalama what?”

That was 26 years ago. What keeps her engaged after more than two decades? The students.

“Their curiosity amazes me, and their true interest in knowing makes me want to know and keeps me questioning and finding out,” Stevens-Truss said. “They make me laugh daily.”

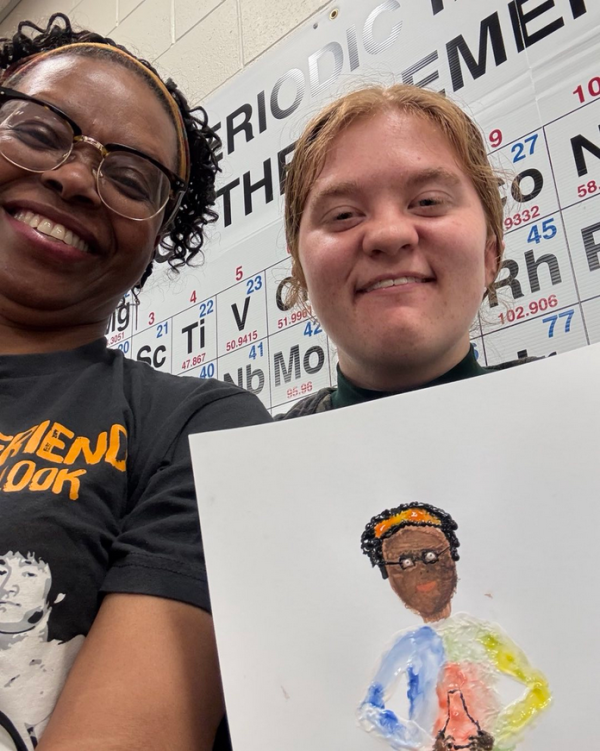

Her impact extends far beyond K. The 2023 ASBMB Award for Exemplary Contributions to Education recognized her decades of work on classroom and social issues affecting student success.

“Being selected for this award was incredibly humbling,” she said. “It also helped validate my career.”

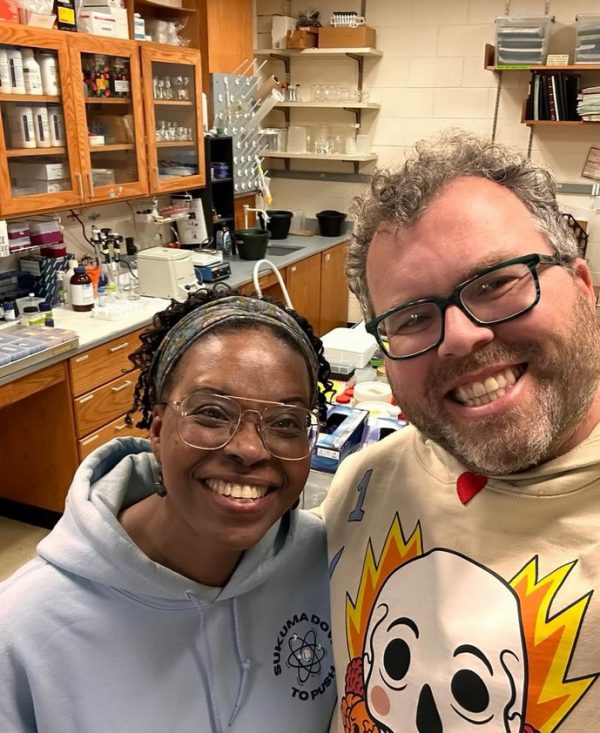

That commitment to student success has taken many forms. In 2016, she received K’s highest teaching honor, the Florence J. Lucasse Lectureship for Excellence in Teaching. In 2018, she was named the College’s director of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Inclusive Excellence grant, awarded to K’s science division. She’s also been a faculty leader for Sisters in Science, a student organization that visits local schools to encourage young women to pursue science; and Sukuma, a peer-based study group for students of color in the sciences.

A Message for the Next Generation

When she was asked what message she hoped her students would carry forward, Stevens-Truss didn’t hesitate, though she acknowledged it might sound clichéd.

“Truly, follow your dreams,” she said. “Don’t let naysayers tell you that you don’t belong and that you can’t.”

She encourages students to ask themselves key questions: How did you get here? Why do you want to be here? Who inspires you? Who gives you the brutal truth? Who supports you when you’re down?

“Answers to these questions will help keep you on track,” she said.

Her advice for finding your passion is simple yet profound.

“The thing that you go to bed at night thinking about, the one that gets you up in the morning ready to go do it, is your passion and what you should do. Make a career out of that and you’ll be happy.”

It’s advice that comes from experience. Stevens-Truss never stopped being that curious kid who wanted to know why and how. She just found a way to build a life and help hundreds of students build theirs around asking those questions.

As she puts it, “Figuring out how and why something changed, to this day, brings me joy, so I think being a scientist is what I was made to be.”