What began as a year on study abroad at the Universidad de Extremadura in Cáceres, Spain, ended in an international triumph for Annaliese Bol ’26, a Heyl scholar from Kalamazoo College.

Bol, a biology and Spanish double major, blueprinted a bee hotel—a small structure designed to provide nesting, shelter and a safe space to lay eggs for solitary pollinators—and entered it into the Insectopia Festival held from June 2–6 in Jarandilla de la Vera, Spain. The event included a contest among representatives of eight universities across Europe to see who could diagram the best insect hideaway while contributing something educational to humans and helpful to local pollinator health and biodiversity.

The design for Bol’s hotel featured a honeycomb pattern with a QR code that could lead interested passersby to the Insectopia website to learn more about the organization and how it supports pollinators.

“Trying to implement large-scale change to support bees is very difficult,” Bol said. “My project’s goal was to lead people to little solutions that hopefully would compound into something bigger.”

The only problem was that she was returning to the U.S. on June 5, while the festival was still ongoing. However, with some community engagement support from a professor and a master’s student, Bol and her team won the contest.

“I was shocked, honestly,” she said. “I was traveling when my teammates called and asked, ‘Have you checked your email? We won!’”

Bol’s reward is that Insectopia is now building her design, which measures about 18 inches high by 18 inches wide. It includes paper straw and wood blocks that will be important to pollinators in Spain because of its arid climate, especially with a lack of tall trees where pollinators normally can nest. The fact that the bee hotel directs others to the Insectopia website is important, too, as judges required entrants to include a plan for activating the community.

“I like insects, but the artistic part of the project appealed to me because I don’t get to think creatively every day with my studies,” Bol said. “I also liked doing the research to figure out the best materials, and it was educational.”

While abroad, Bol began working on an intercultural research project in which she developed a composting program at the Universidad de Extremadura to decrease waste. Simultaneously, she created a community garden that local teachers could use as a tool for their classrooms.

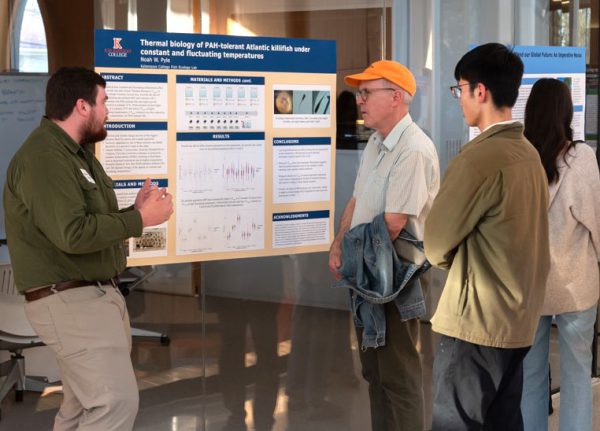

At that time, some of her contacts, including a professor, mentioned the Insectopia contest, although Bol initially didn’t give it another thought. An Insectopia director later asked Bol what she would be doing this summer upon returning to the U.S. Her response: Working with Clara Stuligross, assistant professor of biology, on bee research for her Senior Integrated Project.

“He said that Insectopia is all about bees, so I should be involved in it,” Bol said. “I said, ‘OK, cool,’ and they set me up. They gave me all the information and told me the goal was to design an environmentally friendly, but also educational, bee hotel.”

As she reflects on her experience, Bol affirms the idea that study abroad widens one’s perspective and changes how students think about themselves and other cultures.

“It was interesting and fun,” Bol said. “I made a lot of friends among Spanish students and other Europeans as well. It also made me appreciate my home here, too, in certain ways. I feel that in the United States, we have a perception of Europe being a much more advanced place to live. Maybe it was just because I was in a small Spanish town in the countryside, but it made me appreciate how we address problems here. Maybe it’s just from me attending K, but I feel like we’re always asking, ‘Why is something that way?’”

At K, Bol is a cross country runner and a Crochet Club participant. This fall, she would like to form a K chapter of Women in Wildlife, a student organization consisting of women and non-binary people who want to work in wildlife-associated fields. Bol’s varied interests and commitment to community building have served her well both at home and abroad. Her time in Spain highlighted K’s distinctive approach to study abroad, with programs designed to foster that same kind of meaningful engagement she values on campus.

“I met other American students while I was in Cáceres and traveling around Europe,” Bol said. “When we talked about shared experiences, I asked what they did in their free time, and they didn’t have a lot to say. But K, especially in this program in Spain, makes it a goal to get you ingrained in the community. We could say we were tutoring kids or working on our volunteering projects. That really made my experience special.”