Only 6 years old when her family moved to Michigan in 2009, Ifeoma Uwaje ’24 retains a deep love for her home in Nigeria and remembers the pain of losing young classmates to malaria due to a lack of resources and access to healthcare. Emotional visits back home in 2017 and 2022 elicited a deep desire in Uwaje to improve circumstances for her first community.

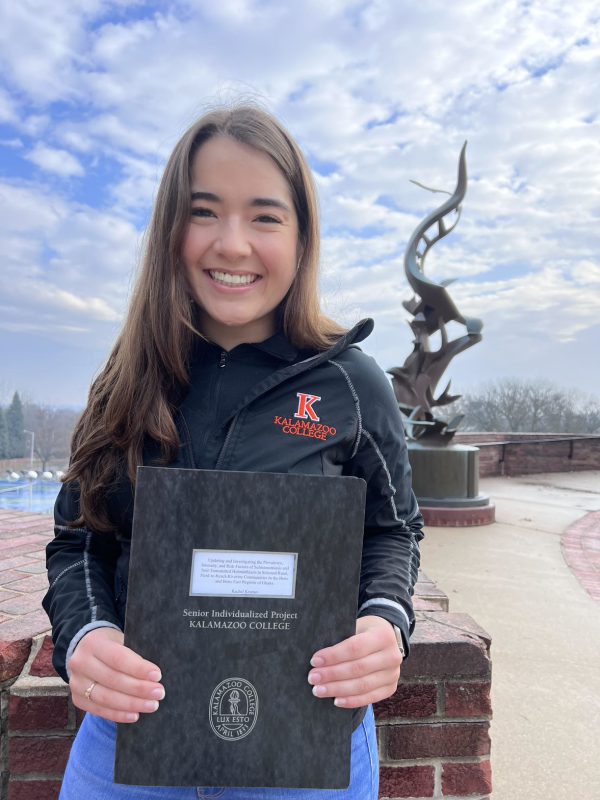

As she anticipates graduating from Kalamazoo College this spring with a degree in biochemistry, Uwaje hopes eventually to combine her commitment to community with her love for science—and her Senior Integrated Project (SIP), currently underway, represents one possible path forward.

Starting college virtually, in the midst of a pandemic, brought home to Uwaje how essential community is for her, and how lonely she was without it. Once she got to campus, she jumped right in, becoming involved with Sukuma Dow, which supports and empowers students of color in STEM, and Kalama-Africa, which creates space to engage with African and Caribbean cultures and experiences.

“The isolation of the pandemic motivated me to find my community here on campus, which made my experiences so much better,” Uwaje said. “I’m grateful for the community I was able to find here.”

Through Kalama-Africa, Uwaje has been part of building a close-knit community and sharing culture and food from different parts of Africa and the Caribbean, both within the organization and with the larger campus community, particularly through events like Afro Fiesta Desi Sol. Both her work as a resident assistant and her involvement with Sukuma Dow have allowed her to experience receiving and offering support.

“I love interacting with my residents and getting to know their stories and connecting with them on a personal level,” Uwaje said. “It warms my heart when my residents come and talk to me about anything, and I’m happy that I can create a safe and welcoming atmosphere for them.

“Sukuma Dow has also been a rewarding experience because when I was a sophomore, it was nice that I had older students that I could go to for advice on how to be a better student or how to do well in a class and for a listening ear those days where things were really stressful. Now that I’m a senior, I’m happy that I can also give advice to younger students, tell them things that I did, reassure them and make them feel supported, and let them know, ‘Hey, you’re not alone. You can do this. You’ve got this. I believe in you.’”

Uwaje has also volunteered at Kalamazoo Loaves and Fishes and participated in science outreach for elementary, middle and high school students in Kalamazoo.

Coming to K, Uwaje intended to major in biology. Quickly, however, classes with Dorothy H. Heyl Professor of Chemistry Regina Stevens-Truss deepened her interest in chemistry, and Uwaje settled on a new major offered from the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

“Being a biochemistry major has been so rewarding,” Uwaje said. “It made everything in my science education make sense. Biology is amazing, and understanding the chemical aspect really exhilarated me because I could learn all of these different reactions that are going on in our bodies and see how they apply to and affect our daily lives.”

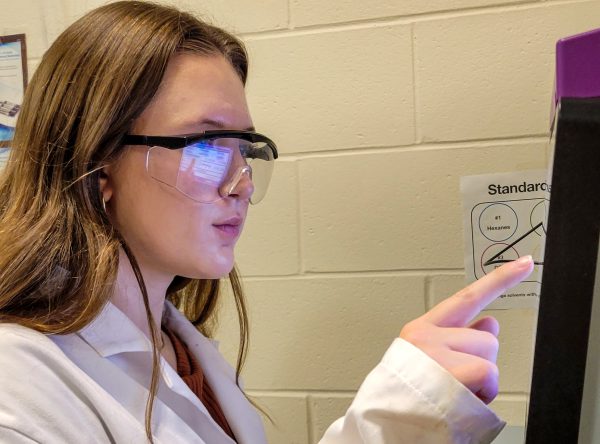

Throughout the summer after her sophomore year and the fall of her junior year, Uwaje conducted research in Stevens-Truss’ biochemistry lab.

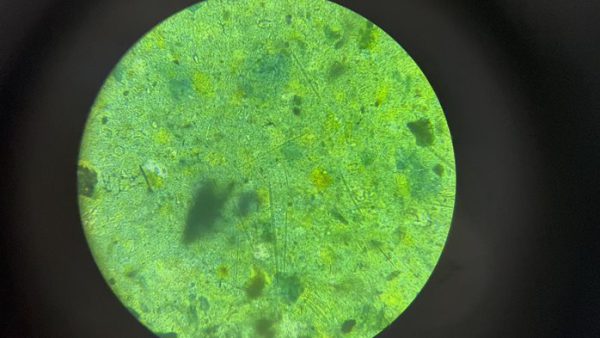

“It’s a dual research project with Dr. [Dwight] Williams’ lab,” Uwaje said. “In Dr. Williams’ lab, they synthesized a series of potential antibiotic hybrid compounds, while in Dr. Truss’ lab, we tested the ability of these antibiotics to inhibit growth of different strains of bacteria.”

While she was specifically testing these antibiotic hybrid compounds on Staphylococcus aureus and E. coli, Uwaje was absorbing a larger lesson and inspiration.

“Working in Dr. Truss’ lab taught me that it’s OK to make mistakes,” she said. “I was very scared coming in because I didn’t want to mess up, but Dr. Truss created an atmosphere where it was OK to make mistakes and I was able to learn from making those mistakes. I’ve been able to take the lessons that I learned and remind myself that things happen, life happens, and the main thing is to keep going and keep learning. Dr. Truss was very calm. Anytime I would mess up something, she’d be like, ‘Oh, that was not quite what you had to do, but that’s OK. Here’s how we’re going to solve that,’ and she was very welcoming and not judgmental about it.”

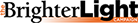

Stevens-Truss suggested that Uwaje, who was interested in medicinal chemistry, could complete her SIP in tandem with her medicinal chemistry class. In the class, students learn how to run computational design and research before choosing a pharmaceutical drug to explore and attempt to improve in small groups.

Uwaje’s group is researching changes that could make anti-malarial drugs more effective and potentially longer-lasting.

“I am looking to derivatize anti-malarial compounds—basically increasing the binding affinity of these anti-malarial drugs to the specific receptor it binds to,” Uwaje said. “I’ll test three to five derivatives to see how these derivatives bind to the receptor, and potentially see if my derivative fits into the receptor well and if it binds tighter to the receptor.”

Although this is a “dry lab,” without actual synthesis and without testing these compounds on biological agents, Uwaje is excited to approach the same basic question of her previous research experience—how can we make this medicine better?—from the other end.

“When I was doing research for Dr. Truss, I was testing compounds that were already synthesized in the Williams lab. The data we produced in the Truss lab would help inform what modifications could maximize the antibiotic’s activity, potency and selectivity. For my SIP, although I’m not synthesizing compounds, I am modifying the structure of these anti-malarial drugs in hopes of increasing the drug’s affinity. In both cases, we’re putting already-known compounds together to potentially make a better drug.

“During the wet lab, we were actually testing these compounds, which is pretty cool. With the computational research, we’re using all of the tools on the computer to modify and make the compounds, thinking, ‘If I add this certain group here, how will it change my compound? Will it make it stronger? Will it make it weaker?’ The technology is cool. I like that I’ve been able to test compounds in the lab, and with my SIP, I like that I’m able to explore different ways I could strengthen and make a better compound.”

And of course, improvements to anti-malarial drugs hold personal meaning for Uwaje.

“There’s certain things that you will never forget in a lifetime,” she said. “I remember my classmates passing away from malaria, so coming into K and given the opportunity to study and design a potential improvement for any drug that I want, those memories ultimately motivated my SIP, because I’ve had many losses from malaria which could have been preventable. Seeing things like that as a young child, I remember feeling so helpless. I knew there were drugs out there that can help prevent malaria, so I decided, what if I look at these drugs, see how their mechanism of action works and see if I could increase the affinity of these drugs to potentially make them even better?”

Stronger medicine alone won’t fix the problem. Knowing that, Uwaje’s plans include a couple years off school before applying to medical school, and eventually returning to Nigeria to improve conditions in any way she can.

“Going back home, seeing the lack of adequate health care and the lack of resources that people have, motivated me from a young age to pursue medicine. My mom was one of the main doctors in my community back in Nigeria. Her contributions to the community actually inspired me to fully commit and pursue this role. I don’t know how just yet, but I know that I’ll do something to help increase access to health care for all back home, because the community needs it. Research, advocacy, medicine—if I could do all of that I would 100 percent do it.”