Kalamazoo College made history today.

At a special celebratory gathering of students, faculty and staff, the College announced the completion of The Campaign for Kalamazoo College, which surpassed its $125 million goal by raising more than $129 million and, in so doing, became the most successful fundraising campaign in K’s history, generating more financial resources than the last two campaigns combined.

“We are grateful to the thousands of alumni, parents, faculty, staff, and friends who made contributions and volunteered time and talent to make this campaign a success,” said President Eileen B. Wilson-Oyelaran.

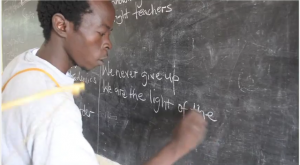

“We also celebrate the deeper meaning of this campaign,” she added, “that a liberal arts education is the best education to enrich a life, in the fullest sense of that word, and the best education to provide lessons that go beyond just employment. There are centuries of evidence to support that notion and now a successful Kalamazoo College campaign to affirm it. And, by the way, a liberal arts education also happens to be the best education not for one job but for multiple jobs, which is likely to be the future for current students.”

Campaign participation was widespread. More than 17,000 donors have made gifts and pledges. Twelve donors committed to gifts of $1 million or more. Sixty-three percent of faculty and staff participated in the campaign.

The ultimate beneficiaries are K students, current and future, who do more in four years so they can do more in a lifetime. The campaign funded five capital projects and seven new endowed faculty positions. Capital projects include the renovations of the Weimar K. Hicks Center and the athletic fields complex and the construction of the Arcus Center for Social Justice Leadership building. Ground has been broken on the new fitness and wellness center, and fundraising will continue for the planned renovation of the College’s natatorium.

The campaign created 30 new funds to support Senior Individualized Project research opportunities for students (the SIP is a graduation requirement at K) and created 35 new permanently funded student scholarships.

“This campaign is about much more than numbers,” said Wilson-Oyelaran. “This campaign is an affirmation of the liberal arts. This campaign is about alumni, parents, and friends who continue to give to Kalamazoo College so that others can benefit from the way that K practices the liberal arts.”

Photos courtesy of Jessie Fales ’18