Newly unearthed diaries dating back at least 80 years are providing a fresh perspective on the Holocaust for a Kalamazoo College faculty member while she hopes to challenge how the world views its refugees.

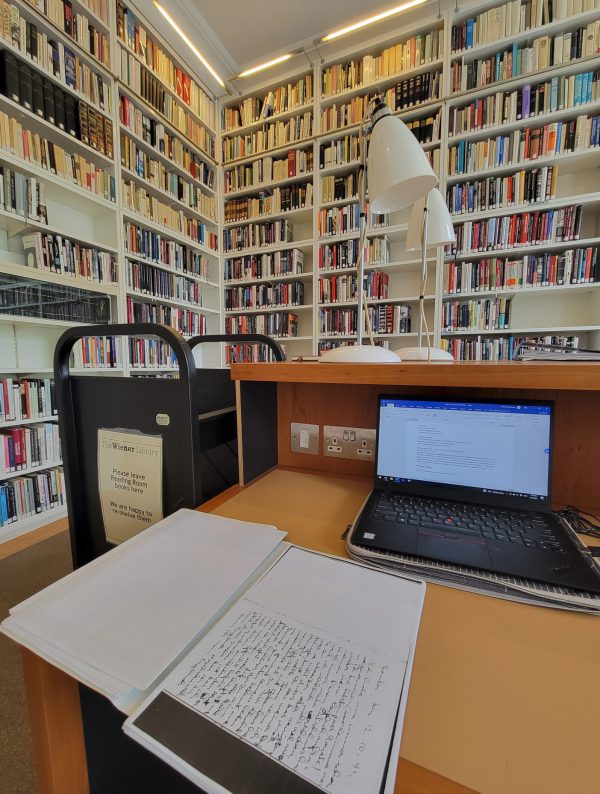

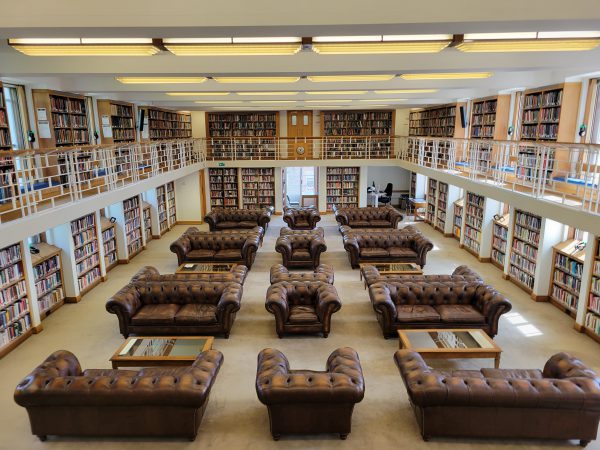

Lucinda Hinsdale Stone Assistant Professor of German Studies Kathryn Sederberg spent a month at the University of London in its Institute of Modern Languages Research. There, with the Miller Fellowship in Exile Studies, she sifted through thousands of passages from Jews who migrated away from Nazi territories in the 1930s and 40s.

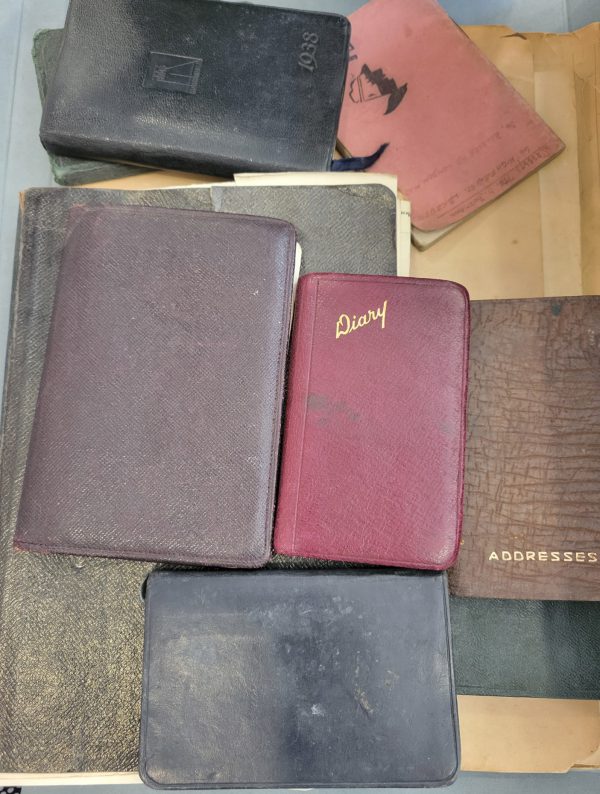

“Being in the archives helps you think about the diary as a material object in a different way,” Sederberg said. “It meant something for people to have this physical book that they carried with them from Vienna to London, or from Berlin to London or New York. They were objects that tied them to home when they’d lost their home and lost family.”

Some of the diaries were written for the writers themselves, some were written with salutations that addressed future generations, and all can help readers better understand life in the moment of the Holocaust.

“People often think of diaries as being private documents,” Sederberg said. “But when we’re talking about Holocaust testimonies, I think people knew they were living through something historic, and often, they were writing for the future, whether it was for themselves to read later or for family members. I just came across a fascinating example of a man who writes to his future grandchildren. He just knew that this would be of interest to future generations. It’s also about preserving the memory and legacy of these individuals, not to romanticize them, but to see as whole persons who had you know, difficulties but also love stories, family drama, school drama, and all the things we identify with today.”

textbooks and novels can’t communicate.

Apart from the individual lives of the writers, the diaries reflect a bigger picture of the Holocaust that goes beyond its most-addressed horrors.

“We usually think about Holocaust survivors as being survivors of the camps and ghettos and the Jews who survived in hiding,” Sederberg said. “These sources are written by the survivors of Nazi persecution. They survived and knew that they were surviving. But it’s also about loss and displacement, and it will help us understand more about diaspora and migration, what it meant to be a refugee, and how refugees understood themselves as refugees and as part of these different refugee communities.”

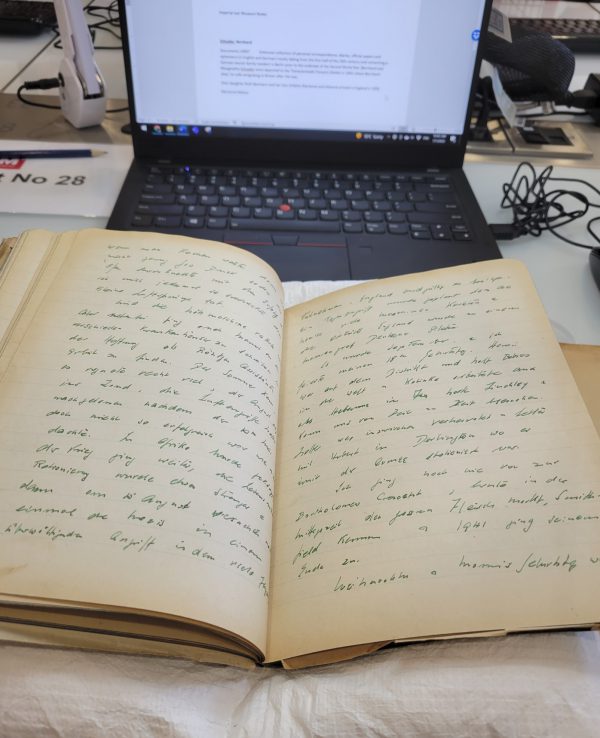

And yet the experience of reading such diaries offers layers of storytelling that textbooks and novels can’t communicate as the writers weren’t assured happy endings.

“When you’re reading diaries, there’s this tension because the writer doesn’t know how their life story is going to end,” Sederberg said. “A novelist or memoirist looks back on their life and is constructing a story. A diary writer doesn’t know if they’re going to survive. They don’t know how their story will end, and when you start reading it, there’s a similar kind of narrative tension to where you want to know what happens.”

Sederberg’s experience is leading to a sophomore seminar that will be offered this winter, Bearing Witness: Holocaust Literature and Testimony. She also expects the project will help her write a book. In the meantime, she has a couple of written articles in progress and will present this fall at the German Studies Association conference. However, she also hopes her project and others like hers will have significance for people beyond academia in addressing worldwide themes surrounding immigration and how refugees are understood or misunderstood.

“As we think about the American reaction to global issues and migration, I think it helps to hear these stories and think historically about what it has meant to be a refugee—to redefine these categories of who is granted asylum,” she said. “Americans didn’t understand who German refugees were. A lot of people didn’t understand that they were persecuted by the Nazis, and I think some of those similar misunderstandings continue when we think about who qualifies as a refugee or being granted asylum status. I think this helps us to better understand what kinds of situations people are fleeing.”