an Oberlin College student from Kalamazoo, were

among the volunteers who collected white clover for

the Global Urban Evolution Project (GLUE).

Read the Science cover story

Two Kalamazoo College biology faculty members, a K student and an Oberlin College student from Kalamazoo were among the volunteers who participated in a global research project that proves humans are affecting evolution through urbanization and climate change.

Professor of Biology Binney Girdler, Associate Professor of Biology Santiago Salinas, Ben Rivera ’18 and Otto Kailing contributed to the Global Urban Evolution Project (GLUE), published Thursday in the journal Science. The investigation shows that white clover plants found in Kalamazoo, for example, will have more in common with others in similar cities around the world than those in rural regions, even local ones. That’s evident because the study shows that clover in many cities produce less hydrogen cyanide as a defense mechanism against herbivores with herbivores being less abundant in cities. Other cities showed no gradient, perhaps because hydrogen cyanide increases clovers’ tolerance to water stress, signaling an environmental driver of evolution prompted by humans with increasing temperatures, additional pollutants and less water.

“We’ve known about these differences for at least a decade now, but it’s always been researched in small or very localized studies, comparing rural versus urban environments,” Salinas said. “The novelty of this work is that it’s being replicated across lots of cities and gradients, most with similar results.”

scientists who collected data for the Global Urban

Evolution Project.

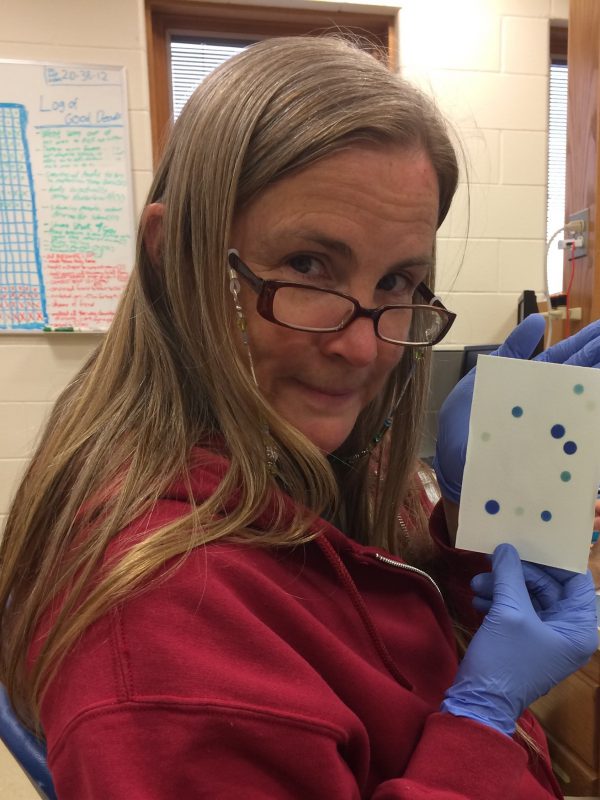

White clover was chosen for GLUE’s research because it’s one of the few organisms present in almost every city. Girdler collected the clover locally along Westnedge Avenue near the Kalamazoo River to do her part alongside 286 other scientists in 26 countries who gathered more than 110,000 clover samples.

Those samples—after being frozen, ground up and analyzed through sample paper and reactive compounds—helped researchers sequence more than 2,500 clover genomes to reveal the genetic basis for their changes in urban areas. The massive dataset produced from the project will be analyzed for years to come, making Thursday’s publication just the beginning of GLUE’s research. With scientists knowing that humans drive evolution in cities across the planet, they can start developing strategies to better conserve rare species, allowing the species to better adapt to urban environments, while scientists also prevent unwanted pests and diseases from doing the same.

“I think the local interest is that this shows we’re not isolated,” Girdler said. “This shows that climate change is real and urbanization is real. This is a good study to show humans have had a huge impact, not just locally, but globally. There’s nothing unique about the Kalamazoo case. We only understand the impact of it when it’s embedded within this giant global study of 160 other cities.”

Marc Johnson and Rob Ness, both biology faculty members at the University of Toronto Mississauga, spearheaded the global project along with James Santangelo, a Ph.D. student. Salinas and Girdler both expressed admiration for that group for organizing the work and maintaining communication throughout the project.

“It’s fun to be a part of it,” Girdler said. “It represents what I think science has to give to the world. It’s connective and it helps us figure out what we should be doing through a global effort. It made me an optimist in the middle of the pandemic.”

“We did it because this was a cool idea and it was nice to be able to help,” Salinas said. “It made me feel like a citizen scientist who added to the body of science without having to worry about prestige.”